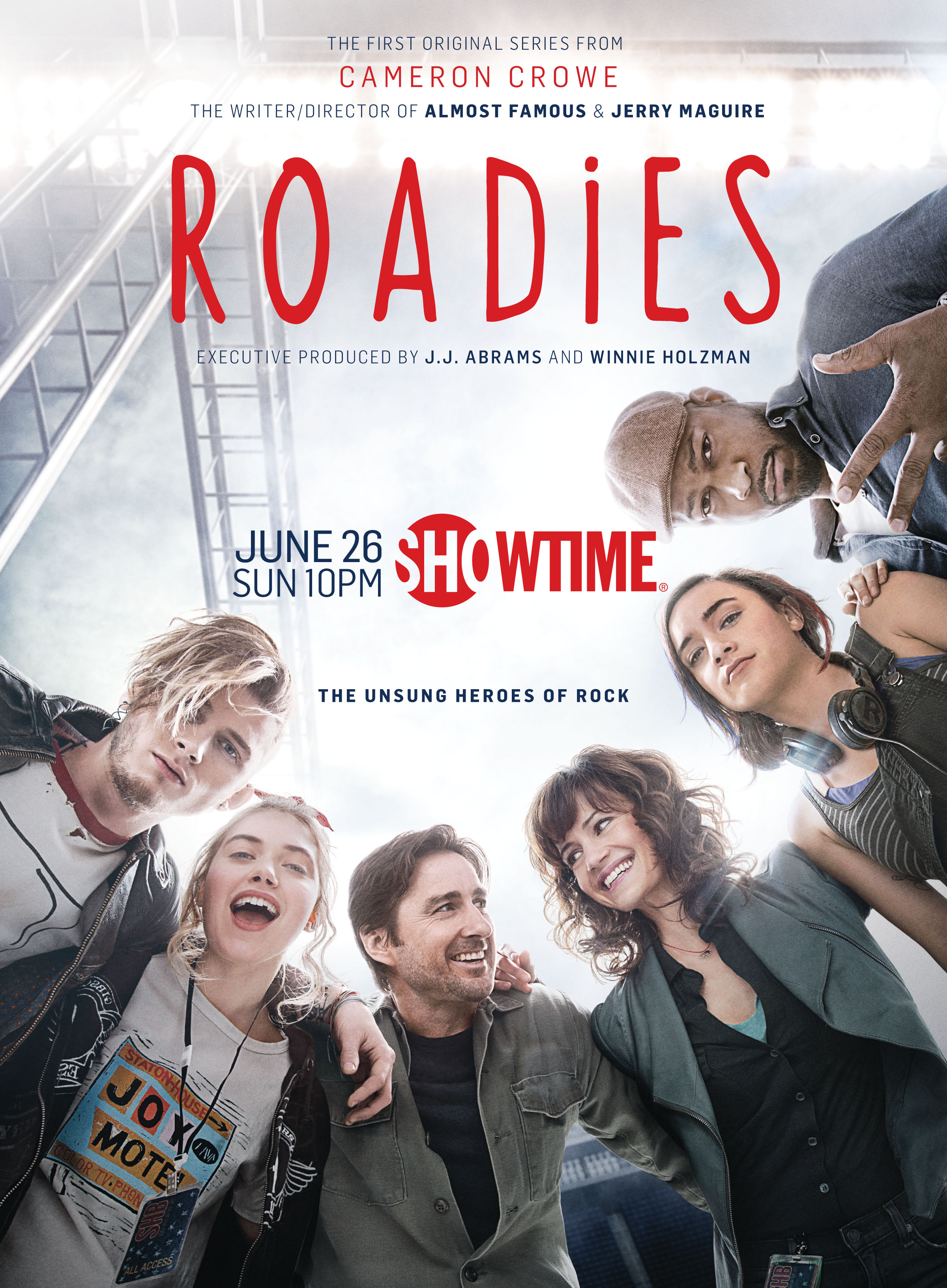

When the director of your all-time favorite movie -- who also won an Academy Award for its screenplay -- announces his first television project, you sit up and pay attention. For me, that director is Cameron Crowe, that movie is "Almost Famous," and that series is "Roadies." Showtime made the first episode available online two weeks early, presumably to build up some buzz before it formally premiered on the network Sunday night. I typically wait until a few episodes have aired before I chime in with my thoughts on a new show, but after watching the pilot several times already, I feel comfortable extolling its virtues to possible fans a little prematurely... and also issuing constructive criticism both to Showtime and to Crowe himself.

"Roadies" follows the backstage crew of a fictional rock band, and each episode will reportedly take place in a new city on their tour. By shining a light on the people whose efforts usually go unsung, the series is setting itself up to be a crash course in music appreciation from the other side of the stage. The passion of these dedicated workers makes the live connection between artist and audience possible, and the use of original music as well as featured "song of the day" tracks during the crew's sound check create a tangible atmosphere of excitement and discovery. I mentally squealed with delight when a scene used only a few instrumental notes of Landon Pigg's magnificently swoon-worthy 2007 ballad "Falling In Love At A Coffee Shop," so I genuinely hope that the series can become a vessel for viewers to find their own kindred songs.

Crowe, undoubtedly influenced by his own travels as a young music reporter, created the show, and he serves as executive producer alongside fellow TV impresarios J.J. Abrams ("Felicity" and "Alias") and Winnie Holzman ("My So-Called Life"). He also wrote and directed the premiere, which is evident in the easy-going appeal and charm of its characters and their dialogue. The cast is at the top of their game; leads Luke Wilson (tour manager Bill), Carla Gugino (production manager Shelli), and Imogen Poots (stagehand Kelly Ann) are pure Crowe naturals. Even guest star Ron White, known for his country-fried snark as a stand-up comedian, gives a memorably heartfelt turn thanks to the quality of the material. They all tackle Crowe's broader moments as well as his nuance with grace and investment, and I'm fully confident that they'll serve as effective ringleaders of this behind-the-scenes circus. Just in its first outing, they've already seen fireworks both figurative and very literal -- not to mention the lead singer's badly-behaved son, fake accents, gunshots, a skateboard chase, a vaguely clairvoyant security guard, and a stalker who gets up close and VERY personal with the lead singer's microphone. All allegedly inspired by actual events... and all before the band even starts to perform!

These antics, while certainly amusing enough to have long-term repercussions, are where "Roadies" could start to hit a few roadblocks if it's not careful. Having a series on cable does allow for a certain amount of creative freedom, but there are a few forced moments that don't really ring true to the rest of Crowe's output. Not one but two awkward sex scenes mark the pilot, and while they're supposed to be awkward in terms of the story and the people involved, they shouldn't be so uncomfortable in the way that they're shown. At the same time, there's a cynical edge that many of the characters are fighting off thanks to corporate intrusion from the record label in their artistic way of life. While this antiheroic tone is common on other, darker shows, it's a weary trend that threatens Crowe's hard-earned optimism. It's almost as if Showtime gave him a quota of subversive benchmarks just to be eligible for their network!

Most troubling is the centralized tension between Shelli and Bill. They're a former couple who now work together respectfully and have a winning professional dynamic, but we can already see the faintest of personal sparks reigniting. Which is problematic, of course, now that Shelli is married. (Is it rude to yawn?) Yes, people are flawed, but wouldn't it be almost radical in its own right to have characters who are good people who are good at their jobs and don't fall into those cliched traps, letting external curveballs do all the work instead? Crowe can successfully resist the urge to be "just another Showtime show" by standing up for his work through his creations. Let them do the walking and talking in a way that feels more authentic to his style, rather than bowing to network pressure. People will keep showing up to watch if they hear Crowe's voice in the words and actions instead of his voice filtered and distilled by "the man."

Overall, the show is a very promising baby that shouldn't be thrown out with the jeopardized bathwater. "Roadies" is smart enough not to shamelessly recycle elements from "Famous," but it carries over much of the same spirit, humanity, and vitality that made its forerunner such a relatable and picturesque love letter to the industry. Holzman, a gifted writer herself, is slated to pen the second episode, with Crowe once again directing. In fact, I would wager that the more episodes he and his inner circle write and/or direct themselves, the more the network will trust his vision beyond just one season. Kelly Ann's arc in this first episode -- and I would imagine the same of each character's journey over time -- reflects the message as well as the potential growth and impact of the series. How do people handle it when their dreams don't match their reality, and what are we supposed to do with those individual goals when they're linked so intrinsically to our career path and the experiences of others? In other words, what does it really take to succeed at something we love, beyond just blind ambition and the best of intentions, when fear and doubt start to creep in?

In true Crowe fashion, a clever, meta-level flourish in the episode's closing minutes finds Kelly Ann making an educated guess and ironically doing the very thing of which she's always questioned the honesty and legitimacy. How well Crowe and company avoid glib answers and explore these interwoven possibilities will determine the longevity and ultimate resonance of the show. If Kelly Ann can be deeply moved enough to take a chance on something that she holds so dear, then Crowe and the rest of his "Roadies" are definitely worth the risk.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Friday, June 24, 2016

"Neon Demon" Lights Up The Art Of Cinema

In the vicious cycle of envy and vanity, which came first? Are people vain because others envy them, or are people envious because of vanity's perceived benefits? This is a question, along with many others, raised by the colorful and controversial thriller "The Neon Demon." The film gives new meaning to keeping up appearances, diabolically satirizing the byproducts of modeling (most pointedly, body image) with razor-like precision. It's a story that's been told many times before -- a young woman, Jessie, moves to L.A. to follow her dreams and discovers their true cost -- but it's never been told quite like this. Fueled by lurid psychology and hauntingly poetic imagery, "The Neon Demon" is a beautiful movie about the ugliness of human nature.

The film's numerous artistic merits place its director, Nicolas Winding Refn, on par with other modern auteurs like Darren Aronofsky, Brian De Palma, and David Lynch. Refn paints "Demon" with a sumptuous visual palette that you literally can't look away from, even during the opening and closing credits. The uses of light and color are exquisite, ranging from near-blinding saturation in scenes where all eyes are on Jessie, to ethereal disorientation in scenes where your own eyes struggle to process the muted frames. These techniques illustrate the moods of the film and the desires of its characters above and beyond other cinematic endeavors in recent memory. In addition, the movie's sublime, immersive soundtrack was provided by composer Cliff Martinez (who contributed an equally stellar score for Refn's 2011 hit "Drive"). The images and the music are effectively paired as the heartbeat and pulse of the story, seamlessly thrusting forward all of its nonverbal tension. Not since Air's compositions for 2000's "The Virgin Suicides" has a contemporary film score felt so vivid and essential. I wouldn't be surprised if the movie garners several technical nominations when award season rolls around, particularly in the art direction, cinematography, and sound categories.

Despite all of its gorgeous trappings, "Demon" would be an empty exercise without key players to carry out its destiny. At only 18 years old, lead actress Elle Fanning is wise enough beyond her years to capture Jessie's tragic allure and aloof naïveté but still remain sympathetic. Her formidable ability to communicate so much range and depth with glances and facial expressions, especially during the photo shoots, is almost intimidating. After roles in 2011's "Super 8" and 2014's "Maleficent," Fanning's first foray into a more mature and demanding role is breathtakingly honest and vulnerable work to rival any other actress in-the-making. Casting a bigger name in the role would have defeated the purpose of the character: witnessing the birth of an ingenue and beholding her ascent.

The other actresses, Bella Heathcote and Abbey Lee, bring an icy edge to their parts as established models who are threatened by Jessie's instant success. Their competitive streak suggests the "dangerous blonde" motif of which film noir was so fond, but they take it to the next level with intentional self-awareness. There are no bimbo models to be found here; instead, these shrewd, calculating femme fatales are in control and will stop at nothing to stay that way. Meanwhile, the cast's secret weapon is Jena Malone, who plays makeup artist Ruby with a calm, confident presence that belies her task to deliver some of the movie's biggest surprises. Her chillingly downplayed scenes in front of mirrors, as she slowly touches up her assorted tones and shades, are a twisted version of donning armor in the battle against her own insecurities and the judgments of the world at large.

Rounding out the cast are stars like Christina Hendricks (from AMC's critically acclaimed series "Mad Men") and the one and only Keanu Reeves, but their screen time is limited to a small handful of scenes that still manage to pack a wallop. Hendricks only appears in one extended sequence as an agent at Jessie's modeling agency, and while it would have been nice to see her do more, she adequately provides a brief voice of reason. This agent may be a corporate woman who prioritizes the business, but at least outwardly, she still has values and hasn't lost her way like the others. At the same time, less of Reeves would have been welcome. His motel owner character is thoroughly despicable and involved in some truly unfortunate scenarios, performed convincingly enough to make you forget his typically laughable "whoa..." demeanor.

These two people are joined by others who glide in and out of the scenery with little fanfare -- a well-meaning suitor, an unyielding photographer, a pretentious designer. It's not lazy or shallow writing; they all act as placeholders who are deliberately treated as disposable on Jessie's misguided path to stardom. Their minimal involvement also establishes a predominantly female perspective among the main characters, which is authenticated by the participation of Refn's co-writers Mary Laws and Polly Stenham. "Demon" could pass the infamous Bechdel test; its women don't talk about men as much as other depictions of models have done. Rather, they understand the elusive power that they hold and consider it their currency. By dissecting that sway in their industry and in society, the film offers some profound insights about the undue pressures that are forced on women. I stop short of calling the movie feminist empowerment, but it's certainly a provocative cautionary tale that feels especially timely in the wake of unrelentingly vacuous "celebrities" on social media.

The disturbing final act, though undeniably hard to watch, resonates beyond just mere shock value. Audiences will undoubtedly find it divisive (about a dozen people walked out of the screening I attended), but it's a barometer for how much they really "get" what the filmmakers are trying to accomplish. Sure, the closing scenes could have easily been depicted with a little more restraint, but it just furthers the study in contrasts that the film was presenting all along (albeit more graphically). It's only then that "Demon" begins to approach the gratuitous and the grotesque, even dipping a toe into them, but the movie never fully submerges into exploitation because it's grounded in its message.

There is no actual demon to speak of, neon or otherwise, except for the one that humanity has made. Our collective fixation on beauty and perfection -- our obsession with them and elevation of them -- is a doomed pursuit, most clearly evidenced by the erotically-charged centerpiece of the film. As Jessie prepares to walk the runway as the final model (the highest honor) in her very first fashion show, she is confronted by a vision and a deep awareness of her potential. All she has to do is surrender to the false idolatry of self above others. In that defining moment, who among us would truly be able to resist such primal temptation? We have all been that demon, and new monsters are created every day when we allow ourselves to focus on the trivial, the material, and the external.

A title like "The Neon Demon" sums up the film perfectly: a brilliantly brutal metaphor about the corruptive and consumptive nature of fame, as well as the desperate lengths that people are willing to go for even the most fleeting taste. Icarus lost his wings by flying too close to the sun, and the same can be said about young angels who stand too close to the spotlight.

Monday, June 13, 2016

Garbage Reaches New Heights On "Birds"

Garbage has always been somewhat of an anomaly in the music industry, so it's only fitting that their new album is called "Strange Little Birds." Lifted from a lyric in their latest collection, this title serves as both imagery and metaphor. Here is a band that has always owned their otherness and hopes that you'll join them by doing the same.

When they first broke onto the scene 21 years ago -- time flies when you're making good music! -- Garbage defined themselves with a smart, sultry, female-led perspective that alternative music at the time was lacking. Well... that perspective was around, but its poster girl was less of a genuine rocker and more of an off-her-rocker joke (*cough, Courtney Love, cough cough*). Shirley Manson, Garbage's frontwoman, operates stealthily under the radar by exuding confidence without arrogance and sex appeal without compromised integrity. Any breaks the band took over their many years together were always issues with creativity and scheduling, versus the in-fighting and scandal that plagued other successful rock acts of the day.

Two decades into their career with no signs of stopping, this background clearly informs the risks and rewards that Garbage earns with "Birds." It's only their sixth album, but it's one that feels right in line with the atmosphere of their previous works: glossy yet brooding, catchy yet incisive. "Birds" delivers on all fronts, managing to feel both very grand (half the tracks approach or surpass the 5-minute mark) and very intimate, with Manson's voice and lyrics as cutting as ever. A sinister piano prelude prefaces the album on opening track "Sometimes," a deceptively minimal song whose skittish electronic backing is simpler and less noticeable than many of the band's arrangements, while the words sneak up on you in pure Garbage fashion. That reminder continues with the polished kick of "Empty," a lead radio single that has the most in common with earlier Garbage hits, but it still strikes a unique chord of its own thanks to Manson's resonant vocals during the chorus. Over the course of her career and notably on this album, it's a rare singer indeed who can alternate between her higher and lower registers and between menacing whispers and powerful declarations -- even within the same track -- and still hold you captive in her thrall.

Elsewhere, homages to the band's earlier sounds are plentiful but original. "Blackout" is a gritty throwback to the darker crunch of their 1995 self-titled debut and its 1998 follow-up "Version 2.0," while "Magnetized" triumphantly reclaims the poppier infusions found on 2001's "Beautiful Garbage" and 2005's "Bleed Like Me." Even with all of this time-hopping, Garbage has never relied on recording studio magic -- they sound exactly the same, if not better, when playing live! Their nostalgic meditations here are just as welcome now as they were the first time around.

That's not to say this album is derivative by any means. "If I Lost You" is a lo-fi exploration of desire and insecurity that borders on the surreal with its layered vocals and trippy digital hiccups. "Night Drive Loneliness" is exactly what its title suggests -- evoking haunting feelings of disappointment in others and oneself with a descending piano motif -- and it's among the highlights of the album's already solid tracklist. Manson is desperate to "understand why we kill the things we love" on "Even Though Our Love Is Doomed," one of the closest things Garbage has ever given us to a more traditional, against-all-odds love song... albeit with their signature downbeat snark. That track's shivery orchestrations effectively build to a more amplified finale. If you're looking for a statement of purpose, for the album or for Garbage itself, look no further than "So We Can Stay Alive." Every moment of the song feels awake and alert -- embracing the band's past and future -- with heavy fire from the drums and guitars coupled with Manson's urgent, insistent lyrics, unquestionably proving their deep alternative roots.

Penultimate track "Teaching Little Fingers To Play" is an unexpectedly tender dissection of childhood dreams versus adulthood's harsh realities, which makes perfect sense in the band's big picture. As Manson laments and comes to terms with the fact that "there's no one around to fix me now," you can't help but think of the youthful demands from a certain track on their very first album... called (what else?) "Fix Me Now." While it may or may not be a deliberate callback showing their growth and maturity in the years since then, as artists and as people, now I have to wonder how many other details on this album are meant to connect the stages of their career. At face value, it's an impressive effort from a reliable band. But when you look a little closer, it's obvious that Manson and Garbage have been "Strange Little Birds" all along, working their way toward this revelatory moment in music. Suddenly, strange isn't such a bad thing after all.

When they first broke onto the scene 21 years ago -- time flies when you're making good music! -- Garbage defined themselves with a smart, sultry, female-led perspective that alternative music at the time was lacking. Well... that perspective was around, but its poster girl was less of a genuine rocker and more of an off-her-rocker joke (*cough, Courtney Love, cough cough*). Shirley Manson, Garbage's frontwoman, operates stealthily under the radar by exuding confidence without arrogance and sex appeal without compromised integrity. Any breaks the band took over their many years together were always issues with creativity and scheduling, versus the in-fighting and scandal that plagued other successful rock acts of the day.

Two decades into their career with no signs of stopping, this background clearly informs the risks and rewards that Garbage earns with "Birds." It's only their sixth album, but it's one that feels right in line with the atmosphere of their previous works: glossy yet brooding, catchy yet incisive. "Birds" delivers on all fronts, managing to feel both very grand (half the tracks approach or surpass the 5-minute mark) and very intimate, with Manson's voice and lyrics as cutting as ever. A sinister piano prelude prefaces the album on opening track "Sometimes," a deceptively minimal song whose skittish electronic backing is simpler and less noticeable than many of the band's arrangements, while the words sneak up on you in pure Garbage fashion. That reminder continues with the polished kick of "Empty," a lead radio single that has the most in common with earlier Garbage hits, but it still strikes a unique chord of its own thanks to Manson's resonant vocals during the chorus. Over the course of her career and notably on this album, it's a rare singer indeed who can alternate between her higher and lower registers and between menacing whispers and powerful declarations -- even within the same track -- and still hold you captive in her thrall.

Elsewhere, homages to the band's earlier sounds are plentiful but original. "Blackout" is a gritty throwback to the darker crunch of their 1995 self-titled debut and its 1998 follow-up "Version 2.0," while "Magnetized" triumphantly reclaims the poppier infusions found on 2001's "Beautiful Garbage" and 2005's "Bleed Like Me." Even with all of this time-hopping, Garbage has never relied on recording studio magic -- they sound exactly the same, if not better, when playing live! Their nostalgic meditations here are just as welcome now as they were the first time around.

That's not to say this album is derivative by any means. "If I Lost You" is a lo-fi exploration of desire and insecurity that borders on the surreal with its layered vocals and trippy digital hiccups. "Night Drive Loneliness" is exactly what its title suggests -- evoking haunting feelings of disappointment in others and oneself with a descending piano motif -- and it's among the highlights of the album's already solid tracklist. Manson is desperate to "understand why we kill the things we love" on "Even Though Our Love Is Doomed," one of the closest things Garbage has ever given us to a more traditional, against-all-odds love song... albeit with their signature downbeat snark. That track's shivery orchestrations effectively build to a more amplified finale. If you're looking for a statement of purpose, for the album or for Garbage itself, look no further than "So We Can Stay Alive." Every moment of the song feels awake and alert -- embracing the band's past and future -- with heavy fire from the drums and guitars coupled with Manson's urgent, insistent lyrics, unquestionably proving their deep alternative roots.

Penultimate track "Teaching Little Fingers To Play" is an unexpectedly tender dissection of childhood dreams versus adulthood's harsh realities, which makes perfect sense in the band's big picture. As Manson laments and comes to terms with the fact that "there's no one around to fix me now," you can't help but think of the youthful demands from a certain track on their very first album... called (what else?) "Fix Me Now." While it may or may not be a deliberate callback showing their growth and maturity in the years since then, as artists and as people, now I have to wonder how many other details on this album are meant to connect the stages of their career. At face value, it's an impressive effort from a reliable band. But when you look a little closer, it's obvious that Manson and Garbage have been "Strange Little Birds" all along, working their way toward this revelatory moment in music. Suddenly, strange isn't such a bad thing after all.

Friday, June 3, 2016

Marvel Vs. Marvel At The Movie Theater

Marvel has a civil war on its hands. The battle facing their own movie franchises is as complicated in the boardrooms of Hollywood as it is in the storied pages of their comics. Barely a decade ago, Paramount had the film rights to Iron Man, Thor, and Captain America; Universal had The Hulk; Sony had Spider-Man; and Fox had the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, and Daredevil. Today, Fox is the only stubborn holdout, relinquishing Daredevil to Netflix in serialized form but refusing to bow down like the rest to Marvel Studios (a.k.a. Disney) in the almighty arena of the movie theater. Never has this been more obvious than the mere weeks between the releases of Marvel's "Captain America: Civil War" and Fox's "X-Men: Apocalypse." Both movies are aiming for box-office gold with top-notch production values, solid acting, and storylines with catastrophic stakes. However, as they set out to prove themselves worthy of their studios' ongoing investment, their separate personalities start to meld into a collective worldview.

"Civil War," like its 2014 predecessor "The Winter Soldier," doubles as a crowd-pleasing superhero blockbuster and an insightful political thriller. Directly connected to the other Marvel films by picking up in the aftermath of the Avengers' previous world-saving efforts, "Civil War" asks us to consider the tangible cost of heroism -- in diplomacy, dollars, and even dead bodies. It pushes the characters to realistic breaking points and back again as they try and fail to reconcile a grim reality. Both sides of the argument are right, but they aren't built to handle that kind of ambiguity, especially in Captain America's patriotic, black-and-white mentality. As always, the character banter is impeccable, with an earned hint of resentment to prove that these heroes are still human behind their tireless, thankless deeds.

Meanwhile, the introductions of Black Panther as well as Spider-Man (Marvel's victory lap around Sony) establish promising future stories but threaten to overcrowd the present one. "Civil War" could have easily been 20 to 30 minutes shorter and still landed all of its plot points. Thankfully, the action sequences are gripping and raw enough to keep things moving. The absence of Steadicam takes us, admittedly off-kilter, right into the fight, and the visual effects aren't distractingly computerized. Oddly, though, the film climaxes twice, like an insecure lover trying to woo and impress impatient summer moviegoers. We get a big clash within the Avengers, then what feels like an eternity later, we get close-quarters combat between Captain America, Iron Man, and Cap's ultimate frenemy Bucky. The first fight is purely physical -- a frantic orgy of action for the masses -- but it's the second fight that packs a more intimate and psychological punch, baring the movie's mind and soul.

The weight of the soul in "X-Men: Apocalypse" is more heavily burdened and tested. The film does offer welcome moments of levity; once again, as with his scene-stealing turn in 2014's "Days Of Future Past," the snarky Quicksilver saves the day in a clever, effects-laden sequence that breaks the tension beautifully. Elsewhere, the movie's not afraid to get dark. I mean, REALLY dark -- nightmarish visions, children in danger, character deaths, and entire cities being laid to waste -- but that authenticity, set against the cultural growing pains of the 1980s, rings truer to the saga's complexities. I may be overly critical, having grown up reading the "X-Men" comics and watching the '90s animated series. But seeing a gargantuan story arc like "Apocalypse" squeezed into a single movie (when it took numerous issues/episodes of the source material) just seems wasteful. Even when minor liberties are taken with the canon and which characters appear when, it risks the continuity of any subsequent storytelling in the same universe. It would be a win-win for the producers to be more faithful to the origins and also trust open-minded audiences, fans and casual viewers alike, to follow their lead.

"Apocalypse" misses another opportunity to lead by being the latest in an increasingly weary trend of super-ensembles that are bursting at the seams. The film does manage to provide great service to existing characters by filling in some of their gaps, especially with Jean Grey, whose younger presence here is far more satisfying than her appearances as an adult in the first three installments. (If you're a fan of the franchise mythology, you'll really appreciate what she accomplishes and anticipate her next move.) Unfortunately, the movie ends up neglecting many of the characters that help this new entry exist in the first place. Apocalypse is treated more like an inciting incident than an overarching villain, while the youthful versions of commanding figures like Storm and Angel get just enough exposition to be recognized when they show up to fight. Olivia Munn, who plays henchwoman Psylocke, has remarked that she turned down the role of Vanessa in the recent smash "Deadpool" because she didn't want to be reduced to "the girlfriend." Yes, Psylocke is intimidating and even trades blows, but this version of her character -- potentially significant down the line depending on which direction the next films will take -- appears out of thin air and barely has any dialogue. At least Vanessa got some screen time and traded witty, on-par barbs with Deadpool!

Overall, you can't entirely blame director Bryan Singer for trying, since he did helm the franchise's strongest entries with "Past" and 2003's "X2: X-Men United." Despite all of the movie's quibbles, Singer possesses a latent power of his own for masterful details. He embraces the meta influence of the films when several students are shown leaving "Return Of The Jedi" at the mall. Their cheeky opinions on its place in that series form a sly, thinly veiled ranking of the previous X-Movies in this series. Singer also employs the opposite end of the spectrum, reclaiming a controversial scene involving Auschwitz with magnificent emotion and elegant action. "Apocalypse" cements him as the go-to director for framing the very real atrocities that birthed these fictional beings.

Here's where things get interesting; the tone and scale of each film cause them to diverge, but the shared message of the films makes them converge again. "Civil War" is more character-focused and straightforward in its parallels to current events, while "Apocalypse" is more content to allegorize a spiritual and societal construct like the end of the world and populate it with fantasy characters and scenarios. Yet at the same time, these movies find more in common when it comes to illustrating the foundations of Marvel's social philosophy. Where they see eye-to-eye is what happens to people -- whether or not they're members of the same team, whether or not they have special abilities -- when they don't work together for the greater good. These cornerstones of belief and humanity make both movies uniquely Marvel, regardless of who produced them. It also reminds us that DC's late-start task of rivaling their scope and interconnection is exponentially more daunting.

At the end of the day, Marvel needs to protect their creative integrity and do something that's been eight years in the making, back to when the first "Iron Man" movie laid the groundwork for their franchise as we know it. They're certainly not hurting for the cash! I'm no legal expert, but shouldn't it be as simple as paying Fox whatever it costs to bring the rights to their prodigal characters under the same production umbrella? Only then can the Marvel Cinematic Universe and its extended properties truly be unified in the way that these stories deserve to be told on the big screen.

"Civil War," like its 2014 predecessor "The Winter Soldier," doubles as a crowd-pleasing superhero blockbuster and an insightful political thriller. Directly connected to the other Marvel films by picking up in the aftermath of the Avengers' previous world-saving efforts, "Civil War" asks us to consider the tangible cost of heroism -- in diplomacy, dollars, and even dead bodies. It pushes the characters to realistic breaking points and back again as they try and fail to reconcile a grim reality. Both sides of the argument are right, but they aren't built to handle that kind of ambiguity, especially in Captain America's patriotic, black-and-white mentality. As always, the character banter is impeccable, with an earned hint of resentment to prove that these heroes are still human behind their tireless, thankless deeds.

Meanwhile, the introductions of Black Panther as well as Spider-Man (Marvel's victory lap around Sony) establish promising future stories but threaten to overcrowd the present one. "Civil War" could have easily been 20 to 30 minutes shorter and still landed all of its plot points. Thankfully, the action sequences are gripping and raw enough to keep things moving. The absence of Steadicam takes us, admittedly off-kilter, right into the fight, and the visual effects aren't distractingly computerized. Oddly, though, the film climaxes twice, like an insecure lover trying to woo and impress impatient summer moviegoers. We get a big clash within the Avengers, then what feels like an eternity later, we get close-quarters combat between Captain America, Iron Man, and Cap's ultimate frenemy Bucky. The first fight is purely physical -- a frantic orgy of action for the masses -- but it's the second fight that packs a more intimate and psychological punch, baring the movie's mind and soul.

The weight of the soul in "X-Men: Apocalypse" is more heavily burdened and tested. The film does offer welcome moments of levity; once again, as with his scene-stealing turn in 2014's "Days Of Future Past," the snarky Quicksilver saves the day in a clever, effects-laden sequence that breaks the tension beautifully. Elsewhere, the movie's not afraid to get dark. I mean, REALLY dark -- nightmarish visions, children in danger, character deaths, and entire cities being laid to waste -- but that authenticity, set against the cultural growing pains of the 1980s, rings truer to the saga's complexities. I may be overly critical, having grown up reading the "X-Men" comics and watching the '90s animated series. But seeing a gargantuan story arc like "Apocalypse" squeezed into a single movie (when it took numerous issues/episodes of the source material) just seems wasteful. Even when minor liberties are taken with the canon and which characters appear when, it risks the continuity of any subsequent storytelling in the same universe. It would be a win-win for the producers to be more faithful to the origins and also trust open-minded audiences, fans and casual viewers alike, to follow their lead.

"Apocalypse" misses another opportunity to lead by being the latest in an increasingly weary trend of super-ensembles that are bursting at the seams. The film does manage to provide great service to existing characters by filling in some of their gaps, especially with Jean Grey, whose younger presence here is far more satisfying than her appearances as an adult in the first three installments. (If you're a fan of the franchise mythology, you'll really appreciate what she accomplishes and anticipate her next move.) Unfortunately, the movie ends up neglecting many of the characters that help this new entry exist in the first place. Apocalypse is treated more like an inciting incident than an overarching villain, while the youthful versions of commanding figures like Storm and Angel get just enough exposition to be recognized when they show up to fight. Olivia Munn, who plays henchwoman Psylocke, has remarked that she turned down the role of Vanessa in the recent smash "Deadpool" because she didn't want to be reduced to "the girlfriend." Yes, Psylocke is intimidating and even trades blows, but this version of her character -- potentially significant down the line depending on which direction the next films will take -- appears out of thin air and barely has any dialogue. At least Vanessa got some screen time and traded witty, on-par barbs with Deadpool!

Overall, you can't entirely blame director Bryan Singer for trying, since he did helm the franchise's strongest entries with "Past" and 2003's "X2: X-Men United." Despite all of the movie's quibbles, Singer possesses a latent power of his own for masterful details. He embraces the meta influence of the films when several students are shown leaving "Return Of The Jedi" at the mall. Their cheeky opinions on its place in that series form a sly, thinly veiled ranking of the previous X-Movies in this series. Singer also employs the opposite end of the spectrum, reclaiming a controversial scene involving Auschwitz with magnificent emotion and elegant action. "Apocalypse" cements him as the go-to director for framing the very real atrocities that birthed these fictional beings.

Here's where things get interesting; the tone and scale of each film cause them to diverge, but the shared message of the films makes them converge again. "Civil War" is more character-focused and straightforward in its parallels to current events, while "Apocalypse" is more content to allegorize a spiritual and societal construct like the end of the world and populate it with fantasy characters and scenarios. Yet at the same time, these movies find more in common when it comes to illustrating the foundations of Marvel's social philosophy. Where they see eye-to-eye is what happens to people -- whether or not they're members of the same team, whether or not they have special abilities -- when they don't work together for the greater good. These cornerstones of belief and humanity make both movies uniquely Marvel, regardless of who produced them. It also reminds us that DC's late-start task of rivaling their scope and interconnection is exponentially more daunting.

At the end of the day, Marvel needs to protect their creative integrity and do something that's been eight years in the making, back to when the first "Iron Man" movie laid the groundwork for their franchise as we know it. They're certainly not hurting for the cash! I'm no legal expert, but shouldn't it be as simple as paying Fox whatever it costs to bring the rights to their prodigal characters under the same production umbrella? Only then can the Marvel Cinematic Universe and its extended properties truly be unified in the way that these stories deserve to be told on the big screen.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)